Ōtagaki Rengetsu

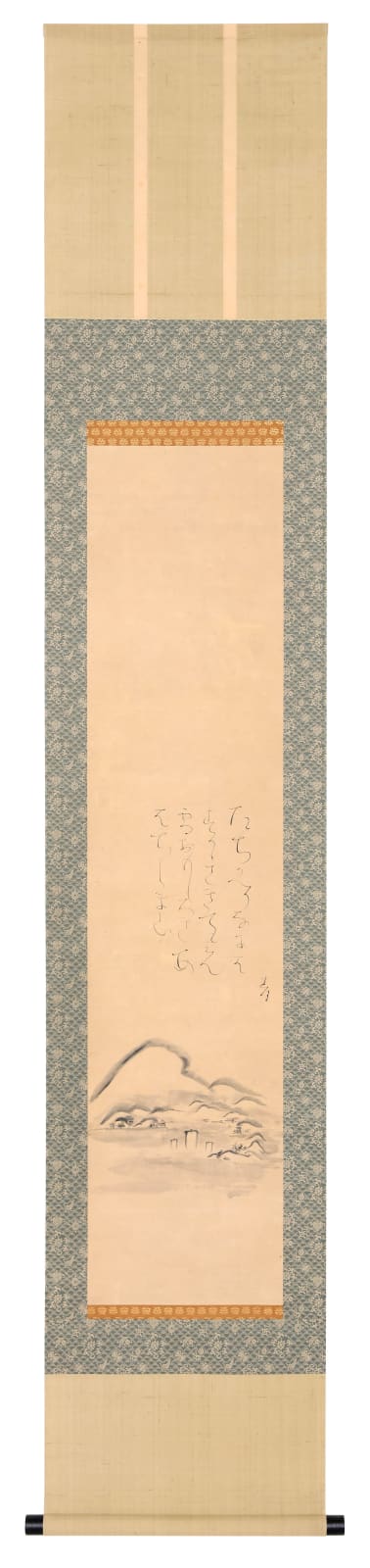

Snow on Awaji Island, with Poem, mid-19th century

Hanging scroll; ink on paper, in silk mounts

Overall size 79¾ x 14¾ in. (203 x 38 cm)

Image size 45¾ x 10¼ in. (116.5 x 326.5 cm)

Image size 45¾ x 10¼ in. (116.5 x 326.5 cm)

T-4346

Further images

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 1

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 2

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 3

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 4

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 5

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 6

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 7

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 8

)

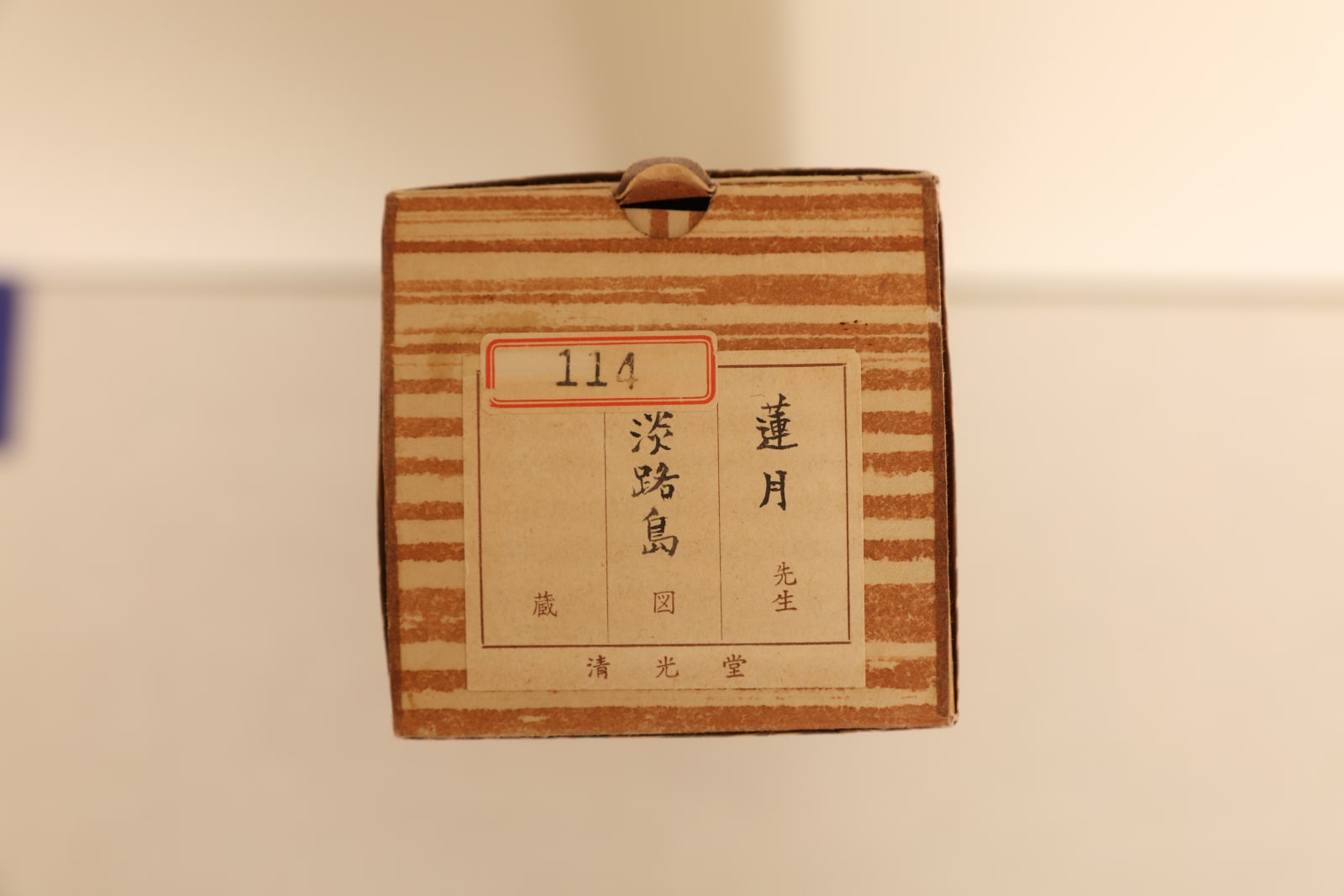

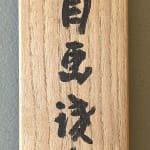

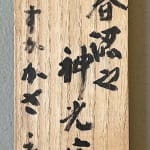

With paulownia-wood kiwamebako (storage box with certification) inscribed 'Awaji painting and poem by the venerable nun Rengetsu', the reverse of the lid inscribed and signed 'Certified in January 1972 by...

With paulownia-wood kiwamebako (storage box with certification) inscribed "Awaji painting and poem by the venerable nun Rengetsu", the reverse of the lid inscribed and signed "Certified in January 1972 by Teien, an elderly priest of the Jinkōin" with a seal Teien and a transcription of the opening lines of the poem; label of the prestigious Kyoto scroll-mounting studio Seikōdō.

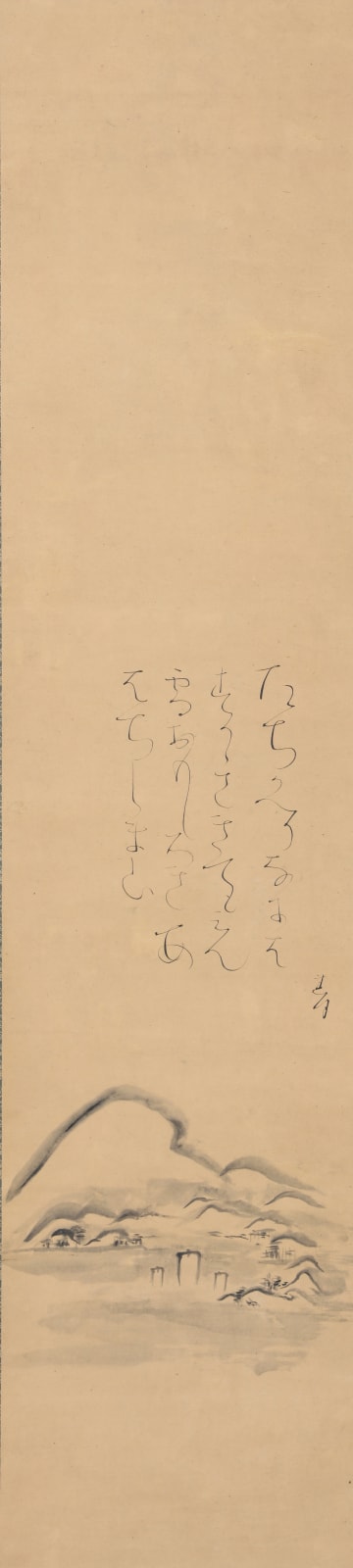

Above a deftly abbreviated landscape depicting sailboats in front of Awaji Island in snow, Ōtagaki Rengetsu has brushed a thirty-one-syllable waka poem in her distinctive threadlike hand:

On my return I

shall wear a rustic hat straw hat

made in Naniwa

so that I can better see

Mount Awaji’s slopes in snow

The poem appears as number 207 in the Winter section of Ama no karumo (A Seaweed Diver’s Harvest), an anthology of Rengetsu’s poems compiled during her lifetime in 1871, see www.rengetsu.com/poetry/primer/.

Adopted shortly after her birth by an official of Chion-in, the Kyoto headquarters temple of the Jōdo (Pure Land) sect of Buddhism, at age eight Nobu (her childhood name) was sent to serve as an attendant at Kameoka Castle, where over a period of nine years she received a thorough samurai education, especially in the martial arts and ninjutsu. Famed both for her ninja skills and as a great beauty, she returned home to marry at age 17 but her later life was marred by tragedy. After losing two husbands, five children, and her stepmother, at age 33 she took vows as a Buddhist nun, assumed the monastic name, Rengetsu, "Lotus Moon," and lived with her father in a sub-temple for ten years until he too died. Aged 43, Rengetsu was now alone. In order to make a living she began producing simple hand-built pots, each incised with one of her poems.

Her rustic ceramics, known as Rengetsu-yaki, were in such demand that it was said that nearly every household in Kyoto had a piece and they were widely imitated. Rengetsu’s poetry, calligraphy, and paintings—mostly dating from her later years—were also admired during her lifetime, as were her frugal lifestyle, peacemaking skills, and charitable donations for famine relief and reconstruction of the city after natural disasters. She remained active to the very end, completing her last painting two days before her death at age 85

Above a deftly abbreviated landscape depicting sailboats in front of Awaji Island in snow, Ōtagaki Rengetsu has brushed a thirty-one-syllable waka poem in her distinctive threadlike hand:

On my return I

shall wear a rustic hat straw hat

made in Naniwa

so that I can better see

Mount Awaji’s slopes in snow

The poem appears as number 207 in the Winter section of Ama no karumo (A Seaweed Diver’s Harvest), an anthology of Rengetsu’s poems compiled during her lifetime in 1871, see www.rengetsu.com/poetry/primer/.

Adopted shortly after her birth by an official of Chion-in, the Kyoto headquarters temple of the Jōdo (Pure Land) sect of Buddhism, at age eight Nobu (her childhood name) was sent to serve as an attendant at Kameoka Castle, where over a period of nine years she received a thorough samurai education, especially in the martial arts and ninjutsu. Famed both for her ninja skills and as a great beauty, she returned home to marry at age 17 but her later life was marred by tragedy. After losing two husbands, five children, and her stepmother, at age 33 she took vows as a Buddhist nun, assumed the monastic name, Rengetsu, "Lotus Moon," and lived with her father in a sub-temple for ten years until he too died. Aged 43, Rengetsu was now alone. In order to make a living she began producing simple hand-built pots, each incised with one of her poems.

Her rustic ceramics, known as Rengetsu-yaki, were in such demand that it was said that nearly every household in Kyoto had a piece and they were widely imitated. Rengetsu’s poetry, calligraphy, and paintings—mostly dating from her later years—were also admired during her lifetime, as were her frugal lifestyle, peacemaking skills, and charitable donations for famine relief and reconstruction of the city after natural disasters. She remained active to the very end, completing her last painting two days before her death at age 85