Iizuka Rōkansai

“Long Life” Leached Bamboo Flower Basket, 1940s-1950s

Bamboo and rattan

Size 11¼ x 10½ x 10½ in. (29.5 x 26.5 x 26.5 cm)

T-4990

Further images

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 1

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 2

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 3

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 4

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 5

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 6

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 7

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 8

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 9

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 10

)

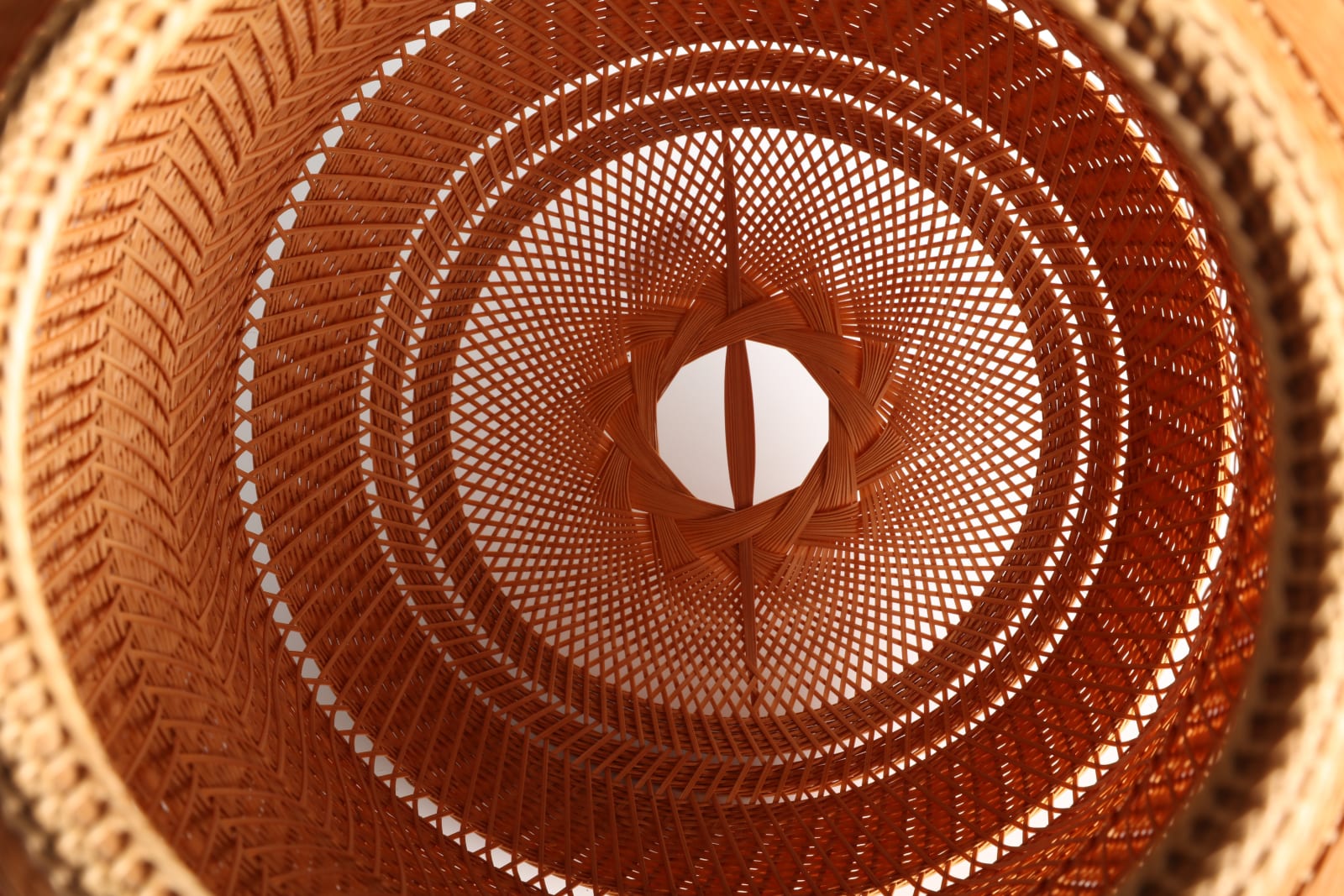

Leached bamboo, rattan; tabane-ami (bundled plaiting), tobigozame-ami (“skipping” mat plaiting), nawame (twining), wrapping, knotting; black-lacquered bamboo otoshi (water container) Signed underneath on a plaque secured at either end within the...

Leached bamboo, rattan; tabane-ami (bundled plaiting), tobigozame-ami (“skipping” mat plaiting), nawame (twining), wrapping, knotting; black-lacquered bamboo otoshi (water container)

Signed underneath on a plaque secured at either end within the tabane-ami plaiting Rōkansai

Comes with its original fitted wood tomobako storage box inscribed outside Hanakago (Flower basket); titled by the artist on the reverse of the lid Banzai (“10,000 Years” or “Long Life”) and signed and sealed Rōkansai

Perhaps the most creative and influential Japanese bamboo artist of all time, Iizuka Rōkansai was born in Tochigi Prefecture the sixth and youngest son of Iizuka Hōsai I and began his training under his father at the age of 12. In his teenage years he briefly aspired to become a painter, but around the time of the family’s move to Tokyo in 1910 he resolved to make it his life’s mission to raise basketry to a higher level of creativity and refinement, immersing himself in the study of Chinese and Japanese literature as well as calligraphy and other aspects of traditional Japanese and contemporary Western art. By the mid-1910s he was accomplished enough to work on pieces that would be signed for many years by his eldest brother and teacher, Hōsai II.

In 1937 Rōkansai, already established as a leader in the craft world, a teacher, and a spokesman for bamboo art, published an article in which he categorized his practice in a similar way to calligraphy or flower-arrangement, as either shin (formal), gyō (semiformal), or sō (informal). A shin basket, he wrote

. . . has an orderly form and is woven with such meticulous care and precision that at first glance one wonders if it really is made from bamboo. Sometimes it is possible to manipulate the material to the extent that the basket’s bamboo-like quality seems to disappear entirely.1

Although the present basket is distinct from the minutely plaited patterned boxes—also classed as shin—that Rōkansai made chiefly for public exhibitions, it falls securely into that category of formality and shares features with several other major works that he created from around 1937: relatively large and generously proportioned, made from artificially leached (whitened) strips of bamboo, partially constructed using variants on gozame (mat plaiting), and usually with a title, chosen by the artist, denoting happiness, prosperity, or (as here) longevity.

Another outstanding feature is the extensive and virtuoso deployment of tabane-ami, an innovation developed by Rōkansai during the mid- to late 1930s, in which bamboo strips split radially from the culm—a method of working unique to artists in eastern Japan—are gathered into bundles of ten or more at the base of a basket, then splayed out into diagonal plaiting and interwoven with other elements to form its sides. Every aspect of this masterpiece of bamboo art, from the meticulous preparation of its raw materials through the subtle modulation of its profile—as sophisticated as anything thrown on a Chinese potter’s wheel—to the meticulous wrapping and knotting at the rim, shows Rōkansai at the pinnacle of his skill and artistry.

Rōkansai used more than one hundred different names for his baskets, starting in the early 1920s, and is said to have reserved Banzai strictly for works in the shin category. The formation of the box signature on the storage box for this piece, especially the middle character Kan, likely points toward a date from the mid 1940s to the 1950s.

Signed underneath on a plaque secured at either end within the tabane-ami plaiting Rōkansai

Comes with its original fitted wood tomobako storage box inscribed outside Hanakago (Flower basket); titled by the artist on the reverse of the lid Banzai (“10,000 Years” or “Long Life”) and signed and sealed Rōkansai

Perhaps the most creative and influential Japanese bamboo artist of all time, Iizuka Rōkansai was born in Tochigi Prefecture the sixth and youngest son of Iizuka Hōsai I and began his training under his father at the age of 12. In his teenage years he briefly aspired to become a painter, but around the time of the family’s move to Tokyo in 1910 he resolved to make it his life’s mission to raise basketry to a higher level of creativity and refinement, immersing himself in the study of Chinese and Japanese literature as well as calligraphy and other aspects of traditional Japanese and contemporary Western art. By the mid-1910s he was accomplished enough to work on pieces that would be signed for many years by his eldest brother and teacher, Hōsai II.

In 1937 Rōkansai, already established as a leader in the craft world, a teacher, and a spokesman for bamboo art, published an article in which he categorized his practice in a similar way to calligraphy or flower-arrangement, as either shin (formal), gyō (semiformal), or sō (informal). A shin basket, he wrote

. . . has an orderly form and is woven with such meticulous care and precision that at first glance one wonders if it really is made from bamboo. Sometimes it is possible to manipulate the material to the extent that the basket’s bamboo-like quality seems to disappear entirely.1

Although the present basket is distinct from the minutely plaited patterned boxes—also classed as shin—that Rōkansai made chiefly for public exhibitions, it falls securely into that category of formality and shares features with several other major works that he created from around 1937: relatively large and generously proportioned, made from artificially leached (whitened) strips of bamboo, partially constructed using variants on gozame (mat plaiting), and usually with a title, chosen by the artist, denoting happiness, prosperity, or (as here) longevity.

Another outstanding feature is the extensive and virtuoso deployment of tabane-ami, an innovation developed by Rōkansai during the mid- to late 1930s, in which bamboo strips split radially from the culm—a method of working unique to artists in eastern Japan—are gathered into bundles of ten or more at the base of a basket, then splayed out into diagonal plaiting and interwoven with other elements to form its sides. Every aspect of this masterpiece of bamboo art, from the meticulous preparation of its raw materials through the subtle modulation of its profile—as sophisticated as anything thrown on a Chinese potter’s wheel—to the meticulous wrapping and knotting at the rim, shows Rōkansai at the pinnacle of his skill and artistry.

Rōkansai used more than one hundred different names for his baskets, starting in the early 1920s, and is said to have reserved Banzai strictly for works in the shin category. The formation of the box signature on the storage box for this piece, especially the middle character Kan, likely points toward a date from the mid 1940s to the 1950s.