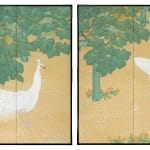

Itō Kinsen

White Peacocks and Fatsia, circa 1914–1915

Pair of four-panel folding screens; ink, mineral colors, and gofun (powdered shell) on silk with gold wash

Size each screen 70 x 110½ in. (178 x 281 cm)

T-4432

Further images

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 1

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 2

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 3

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 4

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 5

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 6

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 7

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 8

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 9

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 10

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 11

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 12

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 13

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 14

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 15

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 16

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 17

)

Several features of this screen pair by Kyoto-based artist Itō Kinsen mark it out as a distinctive example of the experimental, hybrid painting style that emerged in early twentieth-century Japan....

Several features of this screen pair by Kyoto-based artist Itō Kinsen mark it out as a distinctive example of the experimental, hybrid painting style that emerged in early twentieth-century Japan. The use of silk—a material previously very rarely used for screens—is an innovation that appears to date from the later Meiji era (1868–1912), reflecting not only massive expansion of the silk industry but also the taste of a rising generation of clients whose wealth derived from Japan’s new industries: people who combined a conservative inclination toward the traditional with a nouveau-riche fondness for extravagance and display.

The same dynamic between tradition and innovation is apparent in the motifs depicted. Thanks to their association with the Buddhist deity Kujaku Myō-ō, peacocks have been represented in Japanese art for over a millennium, but during the eighteenth century a vogue for exotic birds made them a popular subject for secular painting. The white creatures seen here were likely an import from South Asia, where breeders exploited a genetic condition in peacocks called leucism that sometimes stops pigment cells migrating from the crest to the rest of the feathers during development. It is possible that the screens were commissioned to celebrate the acquisition of these costly rarities.

A taste for the exotic is also reflected in the artist’s choice of plant motifs. Dramatically placed trees, cropped at top and base, first appeared during the Edo period (1615–1868) and grew increasingly popular in subsequent decades, while at the same time a wide range of new plant subjects made their way into the repertoire of Japanese painting, among them the yatsude (Fatsia), rarely seen in the pre-modern period. This striking evergreen usurps the role that might typically have been assigned to pine or other trees and offers the artist an opportunity to deploy his skills in using the rich mineral pigments of Nihonga to depict different textures and tones on either side of the leaves, as well as the intricate clusters of small creamy-white flowers.

Under the leadership of Takeuchi Seihō (1864–1942) a founding father of Nihonga whose mid-life travels in Europe profoundly influenced his development, Kyoto painting in the early twentieth century was open to a wide variety of artistic styles and visions. This screen pair by Itō Kinsen reflects both the bold compositional manner introduced by Maruyama Ōkyo (1733–1795) and the flat, semi-abstract style associated with the Rinpa tradition, as revived by Kamisaka Sekka (1866–1942), while the myriad patches of white that define the ground might even be interpreted as an early version of Japanese pointillism. Nihonga artists continued for several decades to balance competing native and global traditions, creating beautiful works combining elements from the East and West.

The same dynamic between tradition and innovation is apparent in the motifs depicted. Thanks to their association with the Buddhist deity Kujaku Myō-ō, peacocks have been represented in Japanese art for over a millennium, but during the eighteenth century a vogue for exotic birds made them a popular subject for secular painting. The white creatures seen here were likely an import from South Asia, where breeders exploited a genetic condition in peacocks called leucism that sometimes stops pigment cells migrating from the crest to the rest of the feathers during development. It is possible that the screens were commissioned to celebrate the acquisition of these costly rarities.

A taste for the exotic is also reflected in the artist’s choice of plant motifs. Dramatically placed trees, cropped at top and base, first appeared during the Edo period (1615–1868) and grew increasingly popular in subsequent decades, while at the same time a wide range of new plant subjects made their way into the repertoire of Japanese painting, among them the yatsude (Fatsia), rarely seen in the pre-modern period. This striking evergreen usurps the role that might typically have been assigned to pine or other trees and offers the artist an opportunity to deploy his skills in using the rich mineral pigments of Nihonga to depict different textures and tones on either side of the leaves, as well as the intricate clusters of small creamy-white flowers.

Under the leadership of Takeuchi Seihō (1864–1942) a founding father of Nihonga whose mid-life travels in Europe profoundly influenced his development, Kyoto painting in the early twentieth century was open to a wide variety of artistic styles and visions. This screen pair by Itō Kinsen reflects both the bold compositional manner introduced by Maruyama Ōkyo (1733–1795) and the flat, semi-abstract style associated with the Rinpa tradition, as revived by Kamisaka Sekka (1866–1942), while the myriad patches of white that define the ground might even be interpreted as an early version of Japanese pointillism. Nihonga artists continued for several decades to balance competing native and global traditions, creating beautiful works combining elements from the East and West.

Exhibitions

Asia Week New York 2019 Mar