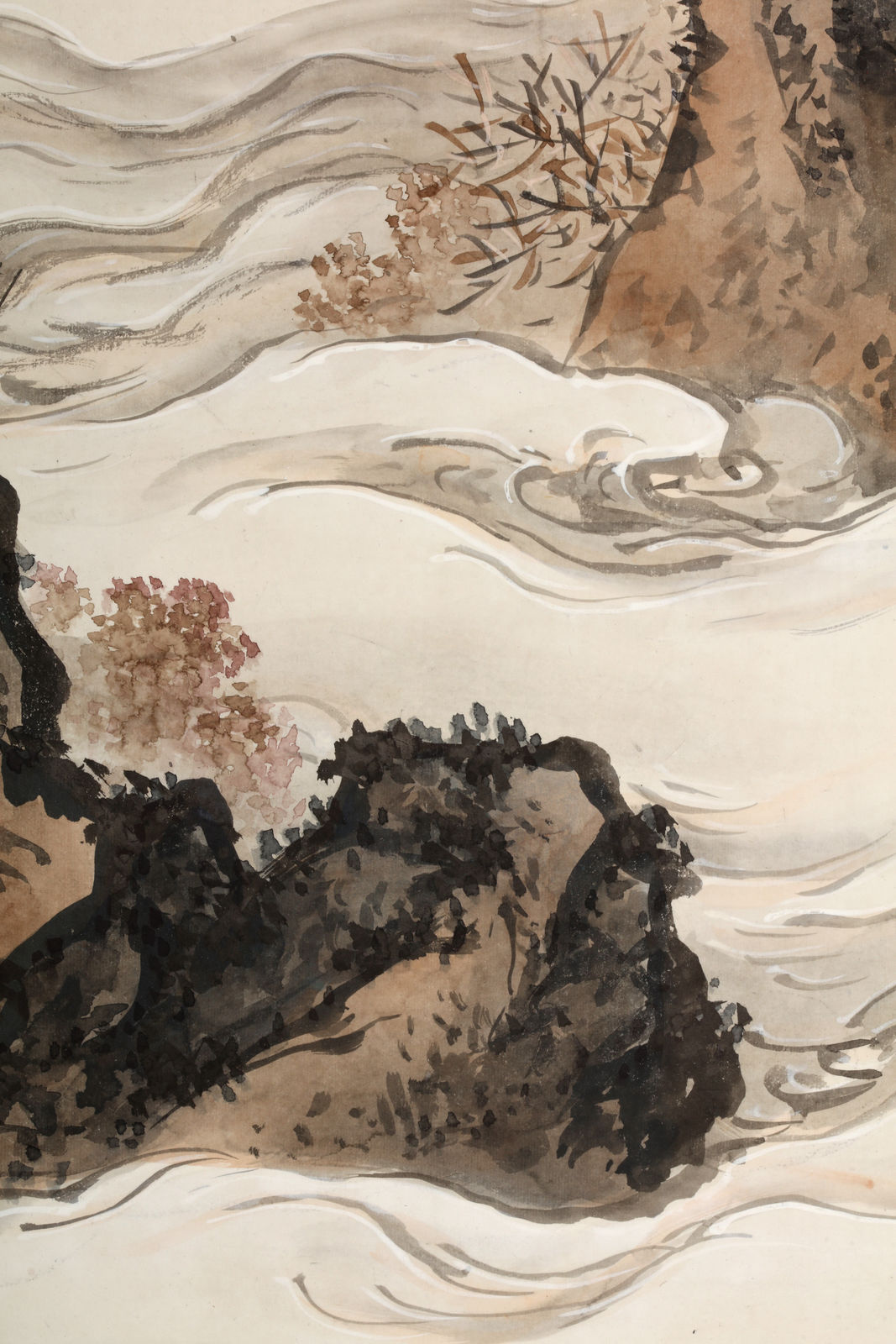

Eiryō Satake

Mountain Landscape, 1916

Pair of six-panel folding screens; ink and light colors on paper

Size each screen 64¼ x 130 in. (163.3 x 330 cm)

T-4576

Further images

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 1

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 2

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 3

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 4

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 5

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 6

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 7

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 8

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 9

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 10

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 11

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 12

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 13

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 14

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 15

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 16

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 17

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 18

)

Born in Asakusa, Tokyo (original name: Kuroda Ginjurō), from age 15 Satake Eiryō studied Nanga (Chinese-inspired Japanese painting) under Satake Eiko (1835–1909), becoming his adopted son in 1899. In 1894,...

Born in Asakusa, Tokyo (original name: Kuroda Ginjurō), from age 15 Satake Eiryō studied Nanga (Chinese-inspired Japanese painting) under Satake Eiko (1835–1909), becoming his adopted son in 1899. In 1894, at age 22, he was one of only seven artists who painted in the presence of the Meiji Emperor as a member of the Japan Art Association. He was a founder-member of several painting associations including the Nihongakai (1898) and—with another famous artist Matsubayashi Keigetsu (1876–1963)—the Nihon Nangashūgakai (1906). His public exhibition career began with a Landscape with Figures at the Fifth National Industrial Promotion Exposition in 1903, and in 1907 he contributed to an unusual set of hagoita (battledores) alongside “Several Eminent Artists”. His career with the Bunten National Exhibition started in 1912 and he showed in other prestigious official salons including the Tōkyō Taishō Hakurankai (1914).

During his national exhibition years Eiryō specialized in the grandiose "neo-Nanga" manner seen in the present pair of screens. The left-hand image is compositionally similar to Azure Mountains and Green Rivers, a work shown at the 1913 Bunten, while Ink Landscape, a pair of six-panel folding screens shown at the 1915 Bunten, is a close match to the present screen in terms of format, subject, scale, ambition, and use of a Western-inflected perspective technique. One can only speculate as to why Eiryō did not participate in the 1916 Bunten but Mountain Landscape, completed shortly before that exhibition’s opening, would have made a striking visual contribution alongside imposing Nanga-style landscape screens by other artists.

In his subsequent career Eiryō exhibited with the Japan Artists’ Association and enjoyed the frequent patronage of the Imperial Household. His teacher’s teacher, Satake Eikai (1803–1874) had been a pupil of the protean Edo-period artistic genius Tani Bunchō (1763–1840) and Eiryō later became a leading scholar and connoisseur of the master’s works. In this regard, it is interesting to consider Eiryō’s screen pairs in the context of Bunchō’s late ink-painting style, including such works a pair of landscape screens on gold ground (dated 1828) in the Gitter-Yelen Collection. Bunchō’s works have a spaciousness and gravity, reminiscent of the masterpieces of seventeenth-century screen and wall painting, that might have inspired Eiryō’s project to revive this most quintessential Japanese painting format as a contribution to the art of his own time.

During his national exhibition years Eiryō specialized in the grandiose "neo-Nanga" manner seen in the present pair of screens. The left-hand image is compositionally similar to Azure Mountains and Green Rivers, a work shown at the 1913 Bunten, while Ink Landscape, a pair of six-panel folding screens shown at the 1915 Bunten, is a close match to the present screen in terms of format, subject, scale, ambition, and use of a Western-inflected perspective technique. One can only speculate as to why Eiryō did not participate in the 1916 Bunten but Mountain Landscape, completed shortly before that exhibition’s opening, would have made a striking visual contribution alongside imposing Nanga-style landscape screens by other artists.

In his subsequent career Eiryō exhibited with the Japan Artists’ Association and enjoyed the frequent patronage of the Imperial Household. His teacher’s teacher, Satake Eikai (1803–1874) had been a pupil of the protean Edo-period artistic genius Tani Bunchō (1763–1840) and Eiryō later became a leading scholar and connoisseur of the master’s works. In this regard, it is interesting to consider Eiryō’s screen pairs in the context of Bunchō’s late ink-painting style, including such works a pair of landscape screens on gold ground (dated 1828) in the Gitter-Yelen Collection. Bunchō’s works have a spaciousness and gravity, reminiscent of the masterpieces of seventeenth-century screen and wall painting, that might have inspired Eiryō’s project to revive this most quintessential Japanese painting format as a contribution to the art of his own time.