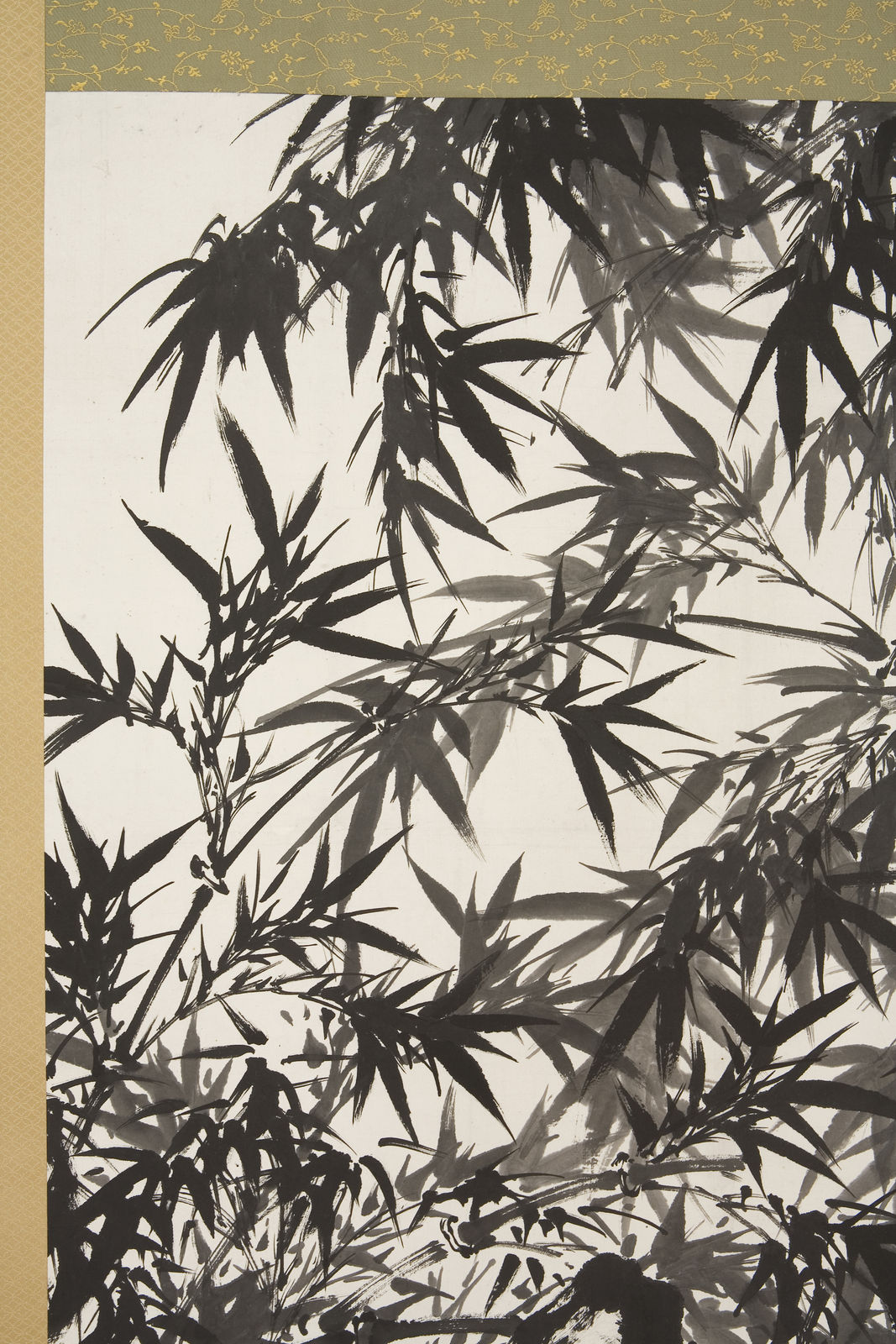

Suzuki Hyakunen

Bamboo, Rocks, and Stream, dated 1881

Hanging scroll; ink on paper

Image size 69¾ x 34¼ in. (177 x 87 cm)

Overall size 98½ x 41 in. (250 x 104 cm)

Overall size 98½ x 41 in. (250 x 104 cm)

T-1302

Further images

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 1

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 2

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 3

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 4

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 5

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 6

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 7

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 8

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 9

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 10

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 11

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 12

)

With a 28-character Chinese inscription (see below for translation), signed Daichin’ō and dated Kanoto-mi chōgetsu (1881, eleventh month) with seals Hyakunen (twice) and Seisei itsumin. With fitted paulownia-wood storage box,...

With a 28-character Chinese inscription (see below for translation), signed Daichin’ō and dated Kanoto-mi chōgetsu (1881, eleventh month) with seals Hyakunen (twice) and Seisei itsumin.

With fitted paulownia-wood storage box, inscribed on the outside Fūchiku zu (Painting of wind-blown bamboo) and on the inside Kore sensō Suzuki Hyakunen-ō no shinseki nari fude chidō shūki chohyō ni in’itsu Shōwa hinoto-u toshi kaheigetsu (This is a genuine work of my revered predecessor Suzuki Hyakunen; his lively, powerful brushstrokes flow rhythmically over the paper. December 1927); further inscribed: Konishi Fukunen-ō kan narabi ni shiki (Examined and inscribed by old man Konishi Fukunen) with seals Konishi Fukunen and Fukunen. Konishi Fukunen (1887–1959) was a pupil of Hyakunen’s eldest son Suzuki Shōnen (1848–1918).

The eclectic Kyoto-born painter and teacher Suzuki Hyakunen turned successfully to the Nanga (often termed “Chinese literati”) style late in his career during a period when Japanese artists wishing to emulate Chinese painting enjoyed increased access to original works from China. Here Hyakunen draws inspiration from the work of Zheng Banqiao (Zheng Xie, 1693–1765), a well-known scholar-official, painter and poet who in 1753 resigned his position as a district magistrate and established himself as a member of the artists’ group known as the Yangzhou Baguai (Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou). Zheng Banqiao is especially admired for his close integration of calligraphy with orchids or bamboo, a visual strategy that Hyakunen aspires here in a strongly expressive style that is all his own.

The connection between the two painters is established not just by visual similarities (although the Chinese artist’s brushwork seems restrained and orderly in comparison to Hyakunen’s) but also because Hyakunen wrote a copy of a poem by Zheng Banqiao in lively calligraphy to the right of the bamboo. The poem—with a bamboo theme—was written on Zheng’s return from a boating excursion on Hangzhou’s fabled West Lake:

Yesterday I returned dead drunk from the West Lake

My clothes messed up, caught on bamboo twigs

Rowing my boat, I reached Jinsha Harbor

Looking back, a clear breeze blew from the pale green hills

With fitted paulownia-wood storage box, inscribed on the outside Fūchiku zu (Painting of wind-blown bamboo) and on the inside Kore sensō Suzuki Hyakunen-ō no shinseki nari fude chidō shūki chohyō ni in’itsu Shōwa hinoto-u toshi kaheigetsu (This is a genuine work of my revered predecessor Suzuki Hyakunen; his lively, powerful brushstrokes flow rhythmically over the paper. December 1927); further inscribed: Konishi Fukunen-ō kan narabi ni shiki (Examined and inscribed by old man Konishi Fukunen) with seals Konishi Fukunen and Fukunen. Konishi Fukunen (1887–1959) was a pupil of Hyakunen’s eldest son Suzuki Shōnen (1848–1918).

The eclectic Kyoto-born painter and teacher Suzuki Hyakunen turned successfully to the Nanga (often termed “Chinese literati”) style late in his career during a period when Japanese artists wishing to emulate Chinese painting enjoyed increased access to original works from China. Here Hyakunen draws inspiration from the work of Zheng Banqiao (Zheng Xie, 1693–1765), a well-known scholar-official, painter and poet who in 1753 resigned his position as a district magistrate and established himself as a member of the artists’ group known as the Yangzhou Baguai (Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou). Zheng Banqiao is especially admired for his close integration of calligraphy with orchids or bamboo, a visual strategy that Hyakunen aspires here in a strongly expressive style that is all his own.

The connection between the two painters is established not just by visual similarities (although the Chinese artist’s brushwork seems restrained and orderly in comparison to Hyakunen’s) but also because Hyakunen wrote a copy of a poem by Zheng Banqiao in lively calligraphy to the right of the bamboo. The poem—with a bamboo theme—was written on Zheng’s return from a boating excursion on Hangzhou’s fabled West Lake:

Yesterday I returned dead drunk from the West Lake

My clothes messed up, caught on bamboo twigs

Rowing my boat, I reached Jinsha Harbor

Looking back, a clear breeze blew from the pale green hills

Exhibitions

Basel Design 2019