Yamamoto Chikuryōsai I

Painting Retreat in a Bamboo Grove, 1927

Hanging scroll; ink and colors on paper

Overall size 75 x 16 in. (191 x 41 cm)

Image size 51½ x 12 in. (130.5 x 30.5 cm)

Image size 51½ x 12 in. (130.5 x 30.5 cm)

T-4936

Further images

Signed and dated at upper right Shōwa teibō haru Tenba Sanbō ni oite Chikuryōsai ga (Painted by Chikuryōsai at the Heavenly Horse Mountain Hut in spring 1927); seals: Yamamoto Ryō...

Signed and dated at upper right Shōwa teibō haru Tenba Sanbō ni oite Chikuryōsai ga (Painted by Chikuryōsai at the Heavenly Horse Mountain Hut in spring 1927); seals: Yamamoto Ryō and Chikuryōsai; with a further seal at lower left

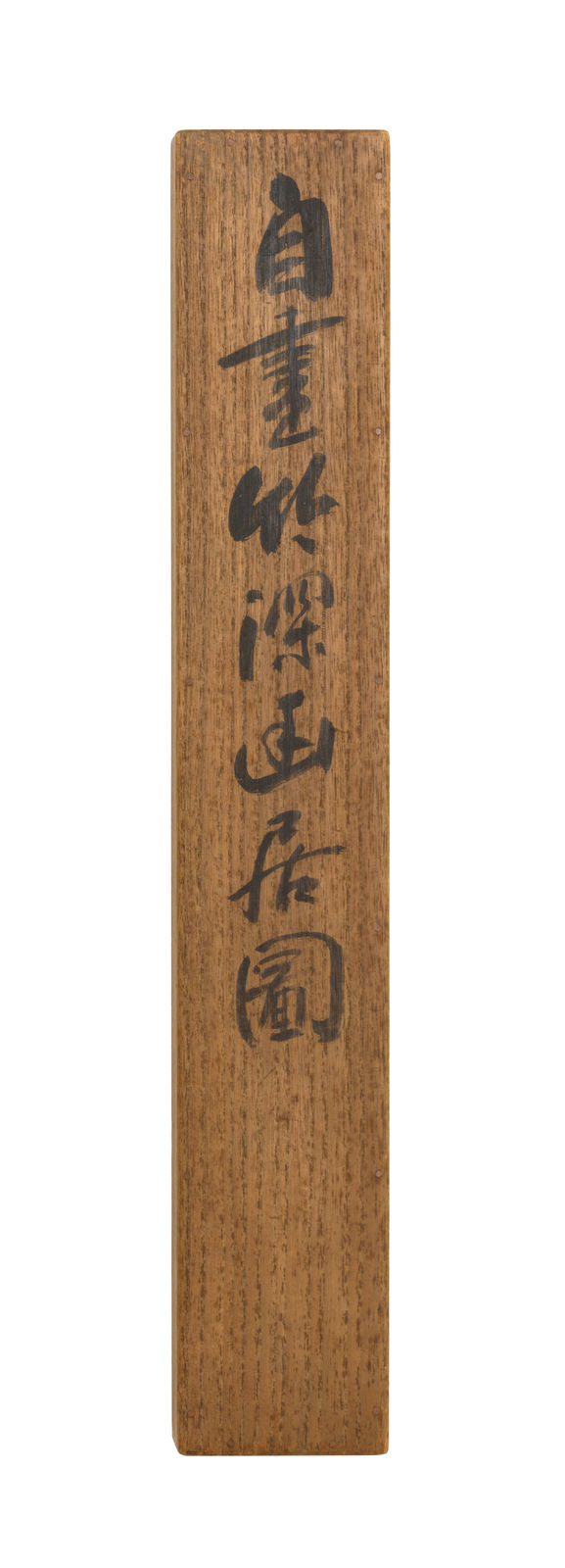

Comes with a wood tomobako storage box inscribed outside Jihitsu chikushingakyo zu (Painting of my deep bamboo painting retreat, brushed by myself); inscribed and signed inside Shōwa teibō haru Chikuryōsai (Chikuryōsai, spring 1927); seal: Chikuryōsai

Yamamoto Chikuryōsai I was one of the leading bamboo artists of his day and a frequent prizewinner at major exhibitions both in Japan and overseas, including the Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes held in Paris in 1925. In 1929 he was one of a handful of bamboo specialists who were admitted to the Teiten national fine arts exhibition, marking an important step toward the recognition of bamboo as a legitimate artistic medium. In the same year, he ceded the name Chikuryōsai to his eldest son; he would use the name Shōen from then until his death.

In Japan, the development of bamboo art was intimately linked to the fashion for sencha, a style of tea drinking introduced to Japan from China in the early seventeenth century. In sencha, a translucent tea is made by steeping whole leaves in hot water, in preference to matcha, powdered, dark-green leaves whipped with a bamboo whisk into a frothy beverage for chanoyu, the traditional “tea ceremony,” as it is still sometimes referred to outside Japan. Sencha practice mandated that the tearoom should be exclusively decorated with flower containers made from bamboo, not just in the summer months (as with chanoyu) but throughout the year. Sophisticated practitioners of sencha, chiefly in the western cities of Kyoto and Osaka, immersed themselves in many other aspects of what they perceived to be most refined in their imagined version of contemporary Chinese culture, including calligraphy, classical verse composition, and painting.

Brushed at the peak of Chikuryōsai’s career as a bamboo artist, this lively landscape testifies to his broader culture and espousal of the Chinese ideal of the scholar painter, living in a mountain retreat having abandoned worldly affairs. Associated with the Nanga group of artists that flourished from the eighteenth to the twentieth century, this supposedly “amateur” style of painting was soon brought to a high level of sophistication in Japan. Here Chikuryōsai, who painted several such scenes starting in the 1920s, shows himself to be a master of the subtle handling of ink and slight color, using the tradtional Chinese perspective convention of “higher up is further away” to lead the viewer’s eye from the artist’s simple rustic hut—appropriately surrounded by both bamboo plants and bamboo artifacts in the form of a gardener’s basket and a woven fence—toward lofty mountains that express the ideals of scholarly retirement. Likely painted in preparation for a sencha gathering, it would have been an ideal complement to one of Chikuryōsai’s superlatively refined, tall flower baskets.

Comes with a wood tomobako storage box inscribed outside Jihitsu chikushingakyo zu (Painting of my deep bamboo painting retreat, brushed by myself); inscribed and signed inside Shōwa teibō haru Chikuryōsai (Chikuryōsai, spring 1927); seal: Chikuryōsai

Yamamoto Chikuryōsai I was one of the leading bamboo artists of his day and a frequent prizewinner at major exhibitions both in Japan and overseas, including the Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes held in Paris in 1925. In 1929 he was one of a handful of bamboo specialists who were admitted to the Teiten national fine arts exhibition, marking an important step toward the recognition of bamboo as a legitimate artistic medium. In the same year, he ceded the name Chikuryōsai to his eldest son; he would use the name Shōen from then until his death.

In Japan, the development of bamboo art was intimately linked to the fashion for sencha, a style of tea drinking introduced to Japan from China in the early seventeenth century. In sencha, a translucent tea is made by steeping whole leaves in hot water, in preference to matcha, powdered, dark-green leaves whipped with a bamboo whisk into a frothy beverage for chanoyu, the traditional “tea ceremony,” as it is still sometimes referred to outside Japan. Sencha practice mandated that the tearoom should be exclusively decorated with flower containers made from bamboo, not just in the summer months (as with chanoyu) but throughout the year. Sophisticated practitioners of sencha, chiefly in the western cities of Kyoto and Osaka, immersed themselves in many other aspects of what they perceived to be most refined in their imagined version of contemporary Chinese culture, including calligraphy, classical verse composition, and painting.

Brushed at the peak of Chikuryōsai’s career as a bamboo artist, this lively landscape testifies to his broader culture and espousal of the Chinese ideal of the scholar painter, living in a mountain retreat having abandoned worldly affairs. Associated with the Nanga group of artists that flourished from the eighteenth to the twentieth century, this supposedly “amateur” style of painting was soon brought to a high level of sophistication in Japan. Here Chikuryōsai, who painted several such scenes starting in the 1920s, shows himself to be a master of the subtle handling of ink and slight color, using the tradtional Chinese perspective convention of “higher up is further away” to lead the viewer’s eye from the artist’s simple rustic hut—appropriately surrounded by both bamboo plants and bamboo artifacts in the form of a gardener’s basket and a woven fence—toward lofty mountains that express the ideals of scholarly retirement. Likely painted in preparation for a sencha gathering, it would have been an ideal complement to one of Chikuryōsai’s superlatively refined, tall flower baskets.