Mitamura Jiho

Octagonal Jewel Box with Peach Blossom and Butterflies, 1920s

Maki-e red and gold lacquer with shell inlays on a kanshitsu dry-lacquer body

Size 4¼ x 6 x 6 in. (10.7 x 15.2 x 15.2 cm)

T-4742

Further images

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 1

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 2

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 3

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 4

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 5

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 6

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 7

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 8

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 9

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 10

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 11

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 12

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 13

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 14

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 15

)

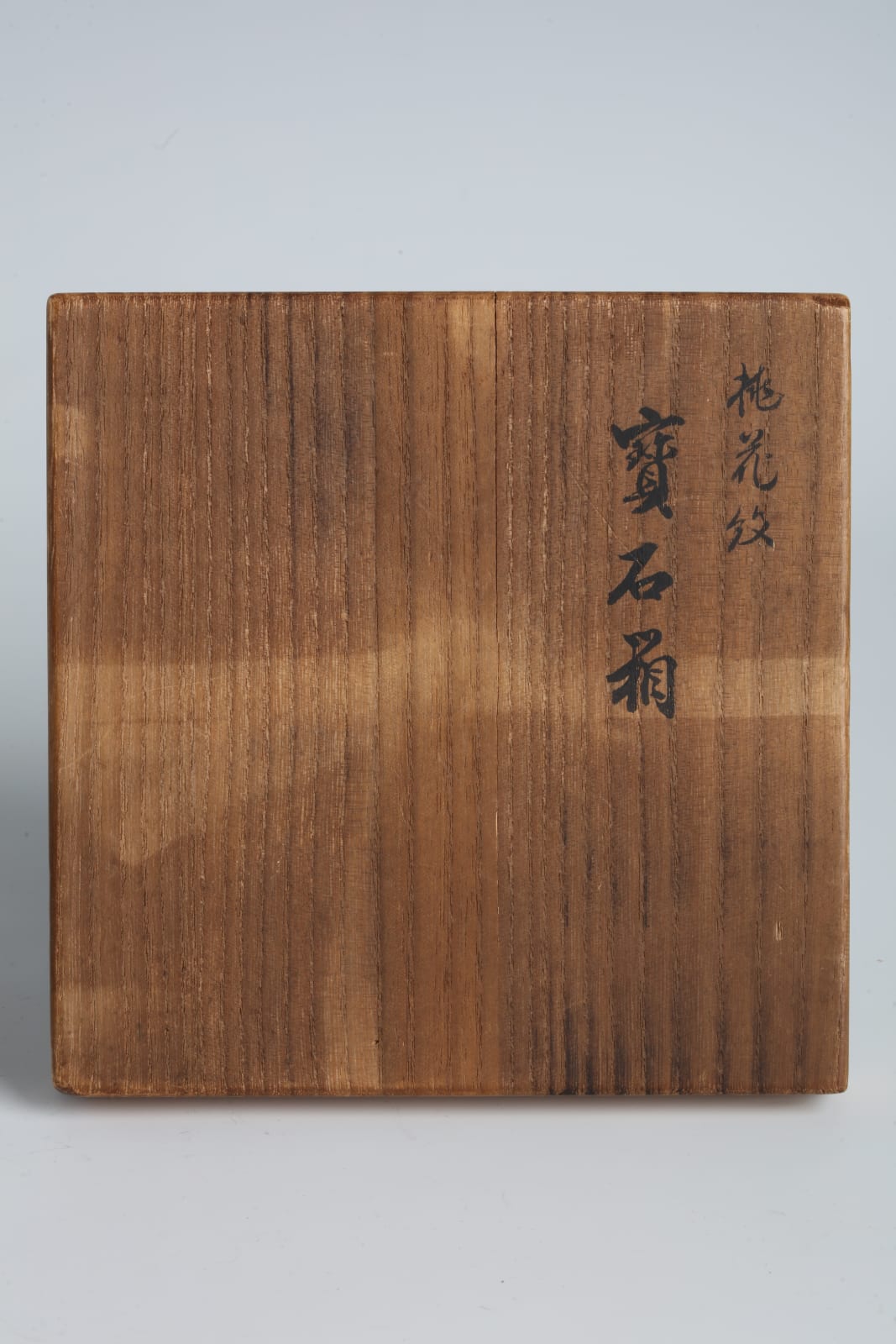

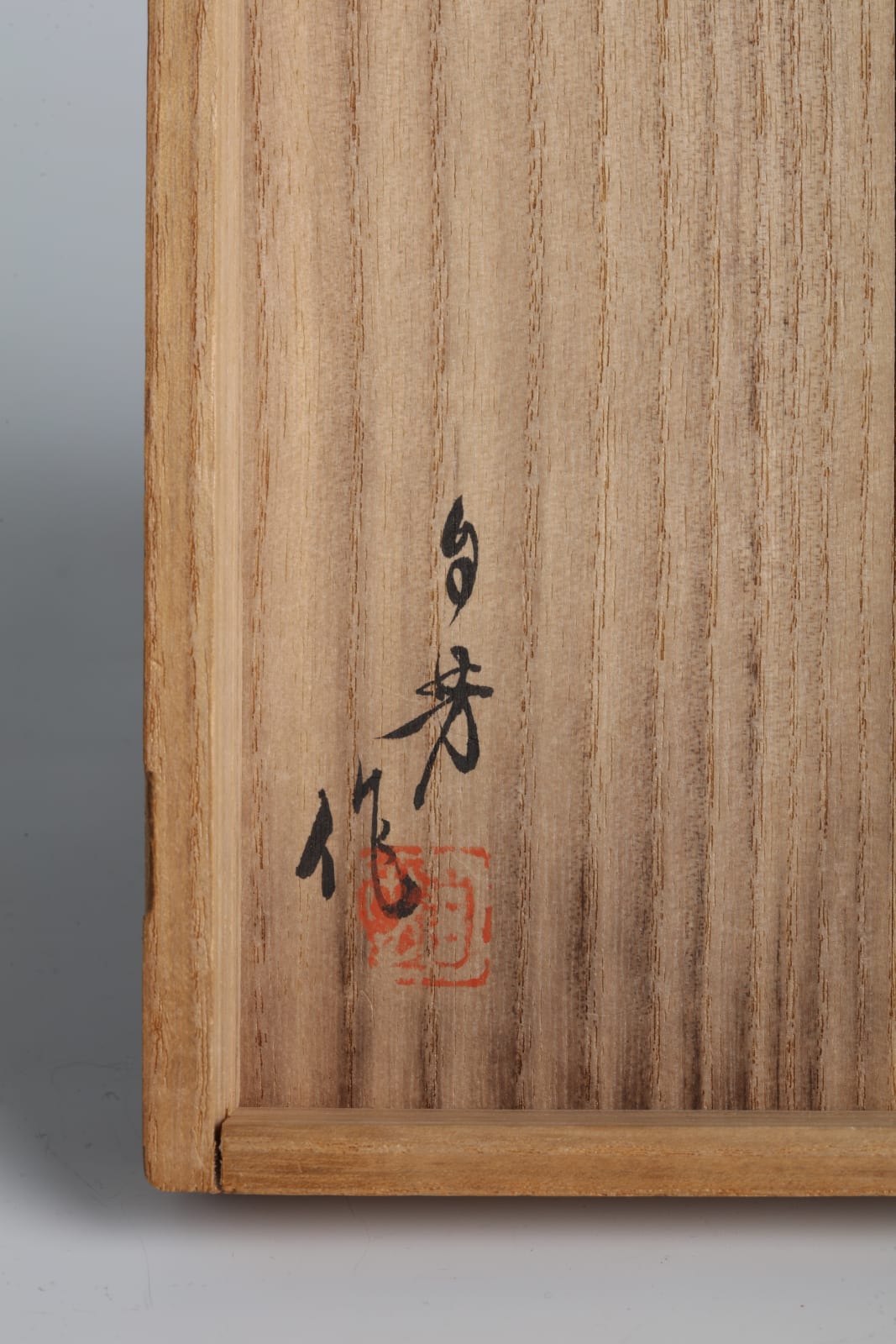

Signed on the base with gold hiramaki-e characters Jiho saku (Made by Jiho). Comes with the original fitted paulownia-wood tomobako storage box inscribed outside in ink Tokamon Hosekibako (Jewel box...

Signed on the base with gold hiramaki-e characters Jiho saku (Made by Jiho). Comes with the original fitted paulownia-wood tomobako storage box inscribed outside in ink Tokamon Hosekibako (Jewel box with peach blossom) and signed and sealed inside Jiho.

An octagonal box with overhanging cover and interior tray, the wood substrate constructed using sashimono (joinery) techniques, the top and sides with a textured ishime (stonelike) black finish, the top with a single stylized multilayered flower motif executed in shell inlay, gold hiramaki-e lacquer, and other techniques, the sides with numerous stylized butterflies in gold hiramaki-e; the interior and base finished in mottled red lacquer, the interior with leaf and floral motifs in gold and silver hiramaki-e

The maker of this box, Mitamura Jiho, was the leading pupil of Akatsuka Jitoku (1871–1936), one of the most outstanding lacquer artists of the early twentieth century. Jiho participated seventeen times in the government-sponsored Teiten national exhibition and its successor iterations for nearly three decades until 1956, but only once showed another piece titled Hosekibako (Jewel Box). That was in 1928 (his very first Teiten, the year after bijutsu kogei [art crafts] were included the exhibition for the first time), when Jiho submitted a hexagonal box that, like this one, was decorated with an elaborate flower on the cover and butterfly motifs on the sides. Although we have so far only been able to locate a small black-and-white photograph of the 1928 box, the present example is so similar that we feel confident in dating it also to the late 1920s. In both cases the main flower decoration is of Buddhist inspiration; this one in particular seeming to echo the hosoge (“treasure flower”) motif, of Chinese origin, often seen in early Japanese Buddhist art.

This masterful box combines technical virtuosity—reflecting the artist’s training under Akatsuka Jitoku (who was among other things a master of shell inlay)—with several influences and trends including the textured lacquer finishes pioneered by Shibata Zeshin (1807–1891) and his followers, along with a renewed interest in early Japanese decorative arts, including lacquer, stimulated by increasing exhibition and publication of temple and shrine treasures that had previously been largely closed to public view.

An octagonal box with overhanging cover and interior tray, the wood substrate constructed using sashimono (joinery) techniques, the top and sides with a textured ishime (stonelike) black finish, the top with a single stylized multilayered flower motif executed in shell inlay, gold hiramaki-e lacquer, and other techniques, the sides with numerous stylized butterflies in gold hiramaki-e; the interior and base finished in mottled red lacquer, the interior with leaf and floral motifs in gold and silver hiramaki-e

The maker of this box, Mitamura Jiho, was the leading pupil of Akatsuka Jitoku (1871–1936), one of the most outstanding lacquer artists of the early twentieth century. Jiho participated seventeen times in the government-sponsored Teiten national exhibition and its successor iterations for nearly three decades until 1956, but only once showed another piece titled Hosekibako (Jewel Box). That was in 1928 (his very first Teiten, the year after bijutsu kogei [art crafts] were included the exhibition for the first time), when Jiho submitted a hexagonal box that, like this one, was decorated with an elaborate flower on the cover and butterfly motifs on the sides. Although we have so far only been able to locate a small black-and-white photograph of the 1928 box, the present example is so similar that we feel confident in dating it also to the late 1920s. In both cases the main flower decoration is of Buddhist inspiration; this one in particular seeming to echo the hosoge (“treasure flower”) motif, of Chinese origin, often seen in early Japanese Buddhist art.

This masterful box combines technical virtuosity—reflecting the artist’s training under Akatsuka Jitoku (who was among other things a master of shell inlay)—with several influences and trends including the textured lacquer finishes pioneered by Shibata Zeshin (1807–1891) and his followers, along with a renewed interest in early Japanese decorative arts, including lacquer, stimulated by increasing exhibition and publication of temple and shrine treasures that had previously been largely closed to public view.